BAGHDAD: In his apartment on Haifa Street in Baghdad — a short walk from the Museum of Modern Art, Iraqi artist Salam Atta Sabri has spread a selection of his recent works across a table.

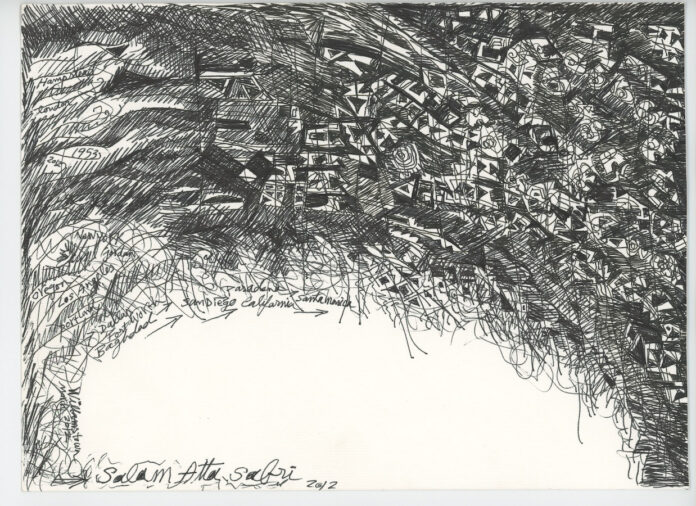

Dozens of intricate abstract drawings in Atta Sabri’s trademark na?ve style depict landscapes filled with palm trees, densely packed buildings, and figures with bright oval-shaped eyes, reflecting their ancient Sumerian ancestry.

Artist Salam Atta Sabri. (Supplied)

The sounds of the call to prayer fill the room as he explains how these drawings resemble a form of therapy for him. Inspired by his own memories, the collective imagination of his homeland and the ancient and modern histories of Iraq, the drawings weave narratives that are at once magical and based on the challenging reality Iraqis have faced over the last few decades due to sanctions, wars, socio-economic upheaval and, now, climate change.

“Despite the death, devastation and neglect the palm tree has faced in Iraq, it resists and remains standing tall, just as our mother country does,” the artist said in a statement for Ruya Foundation, the Iraqi non-profit that facilitated the first public exhibition of Atta Sabri’s work at the 56th Venice Biennale in 2015. “Yet when I draw these palm trees, I feel pain and despair. Since the Iran-Iraq war of the 1980s, our palm tree orchards have been systematically destroyed (by) conflict, neglect and poor urban planning.”

Salam Atta Sabri’s drawings weave narratives that are at once magical and based on the challenging reality Iraqis have faced over the last few decades. (Courtesy of Ruya Foundation)

In many ways, Atta Sabri’s drawings are like a cry for help not only for Iraq’s palm trees, but for the country’s rich heritage. His poignant drawings are his fight against the loss of collective memory.

“Saving palm trees in Iraq from extinction is, for me, a humanitarian issue; they are a fundamental part of our civilization,” he added in his statement.

Atta Sabri was born in Baghdad in 1953. He moved to the US in the early Seventies and studied art at the California State University in Los Angeles. He eventually returned to Baghdad in 1990 (“Right when Iraq invaded Kuwait,” he tells Arab News). A few years later he moved to Jordan where he was given a role at the university teaching ceramics, before returning to his hometown with his wife and two daughters in 2005.

“I returned to Baghdad because it is like a mother; it is the center of my life. Even if it is suffering, it is still my city,” he says.

At that time, it was hard for Atta Sabri to source the basic materials to continue his ceramics practice, so he turned instead to drawing.

“I believe it is my psychological therapy; I believe I am back to my childhood, and I love drawings, so I am drawing again,” he says.

His small, jewel-like works open a window into Iraq’s recent and ancient history, with visual nods to the civilizations that once inhabited the region. They deal directly with returning to a country marred by conflict; once a globally renowned hub for arts and culture, now offering little opportunity for artists.

Salam Atta Sabri, ‘One Thousand and One Nights.’ (Supplied)

He passed the COVID-19 pandemic in Baghdad, producing a series of works in response called “One Thousand and One Nights,” believing that the period of anxious uncertainty the world experienced at that time echoed the tale of Scheherazade from the eponymous classic story collection. When King Shahryar discovered Scheherazade’s infidelity, his anger led him to marry and execute a new woman every day Scheherazade devised a plan to save herself — telling the king a new story each evening but never finishing them. Finally, he gives up trying to kill her.

“Our world is upside down, challenging and constantly difficult, just like ‘One Thousand and One Nights,'” Atta Sabri tells Arab News. “But, like Baghdad, even when she is suffering, the city is still magical.”

Even during times of uncertainty, emphasizes Atta Sabri, there is still wonder to be found in everyday life.